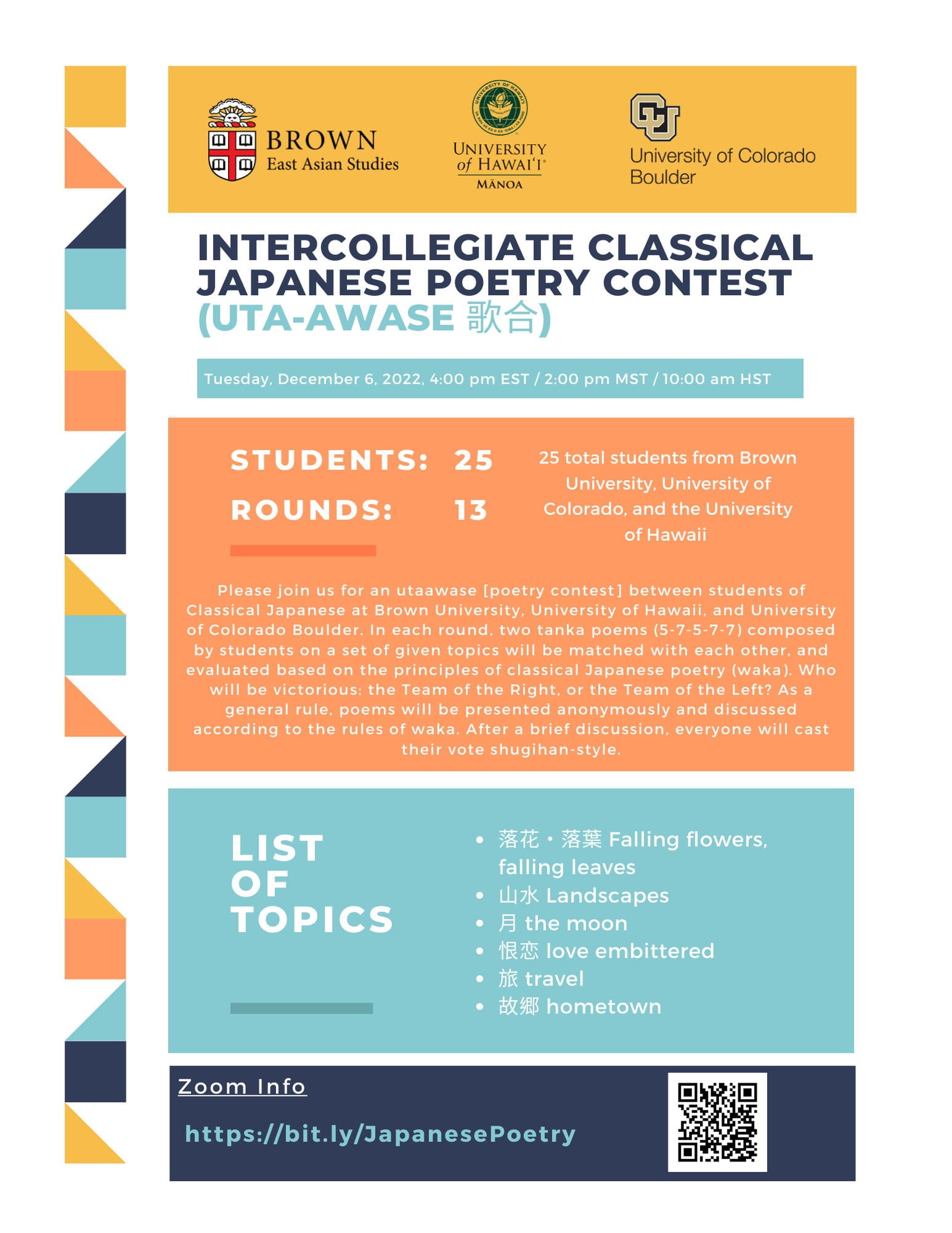

On Tuesday, December 6, JPN461 students participated in the 2022 Intercollegiate Classical Japanese Poetry Contest co-hosted by Prof. Pier-Carlo Tommasi (University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa), Prof. Marjorie Burge (University of Colorado Boulder), and Prof. Jeffrey Niedermaier (Brown University). The first of its kind, the event virtually brought together students from different institutions to discuss original works written according to the etiquette of waka 和歌, that is, traditional Japanese poetry.

The rules were simple: every student wrote a 31-syllable Japanese poem on a given topic, using the specific knowledge acquired during the semester. Then, all poems were anonymously matched in pairs and judged collectively. The audience shared constructive criticism and cast a vote via the Zoom poll feature to decree the winner for each round. The literary contest—or utaawase 歌合, as it used to be called in Japan—was advertised through the Premodern Japanese Studies (PMJS) Listserv and saw the lively participation of people from all around the world, from enthusiastic amateurs to distinguished scholars in the field.

Kiyoe Minami, Research Associate at the Honolulu Museum of Art, was among the guests who attended the meeting and voted on who would win in the matchups. She said: “I was surprised to see that the students were not native speakers of Japanese, yet they were composing poems using the Japanese language of the Heian period [794–1185]. They also used special techniques in the composition of waka poems, such as allusions, pivot words, etc. Furthermore, I could learn a lot from the comments of the professors from the three universities. I hope they hold this event again next year.”

“I was mightily impressed by all of the participants in the intercollegiate utaawase,” said UH Mānoa student Rui Kono. “The content was fresh, yet incorporated classical writing techniques and allusions brilliantly. I could feel that all of the poems had a personal flavor to them, as if they could have only been written by each person. That balance of traditional aesthetics and contemporary worries and celebration was a fusion that brought lots of feelings to my heart as I listened. Through that, I wondered if the participants of utaawase in Heian Japan felt the same way I did just now? It’s a rare experience being able to live history like this, so I must extend my thanks to all of the organizing professors for putting this together and I would love to participate again!”

As Professor Pier-Carlo Tommasi explained, “The arts and the humanities—especially

language-related ones—should serve as a means of self-cultivation and self-empowerment. This is especially true when it comes to classics, whose ‘utility’ is often questioned by the public opinion. In my JPN461 class, I encourage my students not just to memorize ancient grammar rules and patterns, but to take ownership of their learning process through open-ended, creative, and multilingual assignments. My colleagues and I conceived this poetry contest as one such activity.”

Professor Tommasi conducted a similar experiment in English as part of a Literature in

Translation class. “These innovative pedagogies encapsulate our vision to cultivate a globally- informed, culturally-sensitive, and practice-oriented educational model, which makes UH Mānoa the place we all know and love. I hope my students enjoyed the activity and found a renewed interest in traditional and contemporary Japanese culture!” The following quotes are from some of the students who took Tommasi’s EALL271 course and joined the English Utaawase Contest this Fall:

I feel as though I took away quite a lot from this mock poetry contest! It is one thing to read poetry on our own and analyze them during our in-class discussions, but it was an entirely different experience to actually create our own poetry and actively debate on whether or not it properly adhered to the rules of premodern waka. It was an incredibly immersive experience, and overall, it was both very educational and enjoyable. I am a visual learner, and this activity helped give me a much better understanding of the content we were learning.

(Allie St. Sauveur)

The process of hearing othersʼ implementations of waka poetry felt sporty, and served as a method by which we could actively improve upon our own creative expression in the literary confines of wakaʼs rules and traditions. The anonymous nature of the competition added a sense of delightful enigma as we guessed whoʼs work we might be reading. Overall, the activity was incredibly engaging and allowed us to develop a true appreciation for the art form and its modern implementations, as it is still carried out by the Reizei family and others around the world.

(Erik Erixen Nomura)

I really enjoyed our mock utaawase contest, and felt it was a very engaging and valuable experience. I think I learned a lot from the experience, both beforehand when writing my waka poem and during the contest itself. While writing the poem, I found that the main challenge was writing lines that were indirect enough to be poetic/artistic, while also being direct enough that the reader could still understand what I was actually trying to say. During the contest itself, I think the entire class was learning in real time how to better understand the mechanics and themes of waka through the act of critiquing everyone else’s poems. By using the utaawase format of the opposing teams trying to critique their opponents, I think we all developed more discerning eyes for what does and doesn’t work in a waka poem, and thus were able to better understand the make-up and themes of waka poems from both the perspective of the writer and the reader. My main takeaway from this event is that it served both as a technical class, where we improved our writing skills by critiquing others and hearing their comments on our own work, and as a cultural lesson, where we gained a better understanding of historical utaawase competitions through the lens of an actual participant.

(Jordan White)

There are countless poems made by countless poets, each having such deep meaning and

emotions. Despite my interest in these traditional works of literature and reading through them, I have not thought about making traditional Japanese poetry myself. The first opportunity that led me to experience in “actualizing” traditional Japanese poetry was through the assignments in EALL 271 and by composing and thinking the same way that Japanese poets back then thought about their surroundings and how they can convey emotions through words, it provided a more profound appreciation and experience for Japanese literature and culture. […] I believe that studying versus re-creating something conveys two distinct experiences. It is similar to how one can read an event in a history textbook but actually being at the event is totally different.

(Christian Andres)

Related posts:

➢ ‘Speed-dating’ with ancient Japanese artifacts…

➢ Japanese literature students prepare to catalog rare book…